A supply of pipe cleaners, also called chenille sticks, in various sizes and colors provides a great quiet-time activity that will keep almost any child busy for a good, long time. For teaching purposes, pipe cleaners can be formed into a variety of shapes as versatile manipulatives for your tactile students who need to get their hands on something to be able to learn it. The activities listed below can be used interchangeably for letters, numbers, or geometric shapes. Some students may need to try just a few of these activities, while others may want to try all of them… repeatedly.

Bonus tip: It helps to store the pipe cleaners in a shoebox or other container that is large enough to hold several of your students’ artistic creations! You can also take pictures of the more complex creations, enabling the student to dismantle the project and straighten out the pipe cleaners for their next use, while still saving proof of his hard work and imaginative designs.

• Challenge an early learner to duplicate the letters made by Mom or an older sibling.

• Use multiple pipe cleaners to make bigger letters. Using several colors can help younger students recognize the various components of each letter as the separate pencil strokes required to write it.

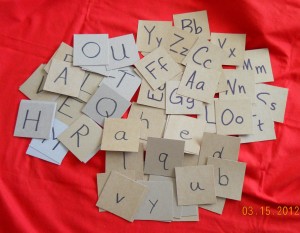

• Make multiples of each letter in various colors and sizes, and then play a matching game by grouping all the matching letters together. Students can also match pipe cleaner letters to other sets of letters: magnetic letters, letter tiles from games, flashcards, ABC books, etc.

• Match upper & lower case letters together as big brother/little brother pairs.

• Make letters to match those shown on letter tiles from games or on letter flashcards (even home-made). Shuffle cards and place stack face down, turning up the top card for the challenge letter, or put letter tiles in a clean sock or paper bag, then draw one tile at random for the challenge letter.

• Another version of the letter challenge game is to make the opposite case letter of the challenge card or tile. If a flashcard shows a lower case letter, challenge the student to make the upper case version of that letter; if a letter tile shows an upper case letter, make its lower case counterpart.

• Show how flipping a lower case “b” can transform it into a “d,” “p,” or “q” to help children learn to differentiate between the letters. The same principal works for turning a lower case “n” over to become a “u,” or turning an upper case “M” over to look like a “W.” Demonstrating that certain letters do have similar shapes can help children understand which is which and be certain they are using the correct one.

• Twist the ends of several pipe cleaners together to make a long line of pipe cleaners and bend it into the shape of cursive letters or entire words in cursive script.

• FEEL the letters blind-folded or with eyes closed (no peeking!) and try to identify them correctly. This can be tricky if the letter is held upside down or backwards, but turning it over and all around will help students learn to identify and distinguish between similarly-shaped letters. Some students may enjoy the challenge of trying to identify letters that are purposely positioned upside-down or backwards.

• Challenge students to “reproduce this pattern” of geometric shapes, numbers, or letters, even repeating the same colors used. This same activity works well for teaching pattern recognition when stringing beads, but mistakes can be corrected more simply in this version by moving a few pieces around, instead of un-stringing the entire project, and can therefore be less stressful for a sensitive student.

• Numbers made from pipe cleaners can be used to illustrate early math problems in a fuzzy, tactile way, providing a helpful transition between the “counting beans” stage and doing written problems.

• Lay a sheet of paper over any flat pipe cleaner creation and rub across the paper with the side of a crayon to create a “rubbing” image of the letter, number, or shape.

See also:

ABC Flashcards

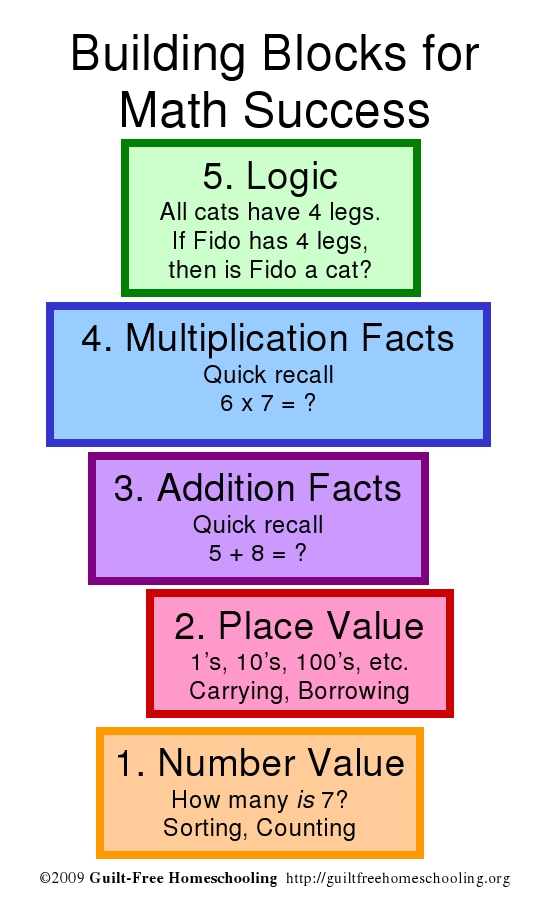

Letter and Number Recognition

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Recent Comments