“Stealth Learning” is my term for lessons that don’t appear to be lessons but can teach as much as or more than their formally planned and structured counterparts. A prime example is letting kids play with manipulatives or learning aids, instead of using them only to illustrate planned lesson activities. Kids will naturally use these materials in ways other than their formal use, but that’s where the stealth learning part comes in. Sneaky, right?

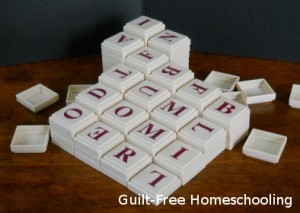

Suppose you subtly leave a set of Scrabble letter tiles lying on the table after the spelling lesson is done (yes, Scrabble tiles are fabulous as tactile spelling manipulatives), or you might casually place the tiles on the table well before they are needed, in anticipation of the spelling lesson (again, stealth teaching mode). Now excuse yourself to go shuffle the laundry, pull something out of the freezer for dinner, or some other valid excuse to leave your student in the same room as the abandoned manipulatives with no other planned activities to occupy his attention. A quick admonition to “wait here, I’ll be right back” may be necessary for some students, but the pile of pieces on the table will beckon to his fingers.

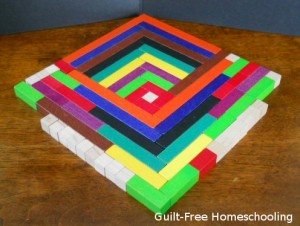

Feel free to delay your return as needed to give your budding explorer ample time to begin stacking, aligning, and organizing the pieces in patterns and structures that will teach him great stealth lessons in spatial math concepts such as height, width, depth, horizontal, vertical, parallel, perpendicular, area, perimeter, volume, and so on. He may not yet know all the proper terms for what he is learning, but those will come through formal lessons later. For now, let him play and experiment and learn through stealth methods.

Lining up letter tiles or math blocks in a checkerboard design is valid learning. Stacking letter tiles in an attempt to create one very tall column is valid learning. Building forts or fences with dominoes is valid learning. Pouring water or cornmeal or rice from one measuring cup to another is valid learning. Drawing intricate designs with a compass is valid learning. Coloring the squares of graph paper to create elaborate patterns is valid learning. Borrowing parts and pieces from your collection of games is creative play and stealthy learning, and sorting them into their respective sources again provides even more stealthy learning. These lessons may not be what the designers of these items originally had in mind, but they are valid lessons, nonetheless.

Think for a moment about the lessons that are learned from the simple act of lining up dominoes on end into curvy rows that can be toppled in rapid-fire succession by one gentle touch on the first domino in the line. First, you learn that it requires a steady hand, precise fine-motor coordination, and siblings who won’t purposely jiggle the table. Second, you learn about spacing the dominoes accurately enough that each one strikes the next with precision when falling, and you learn problem-solving skills when things go awry, causing the process to stop before the entire row has gone down. Third, you learn whether you will experience that momentary thrill of watching your feat of engineering perform in exactly the manner you intended, or if you need to make a few more adjustments to your design and try again. Those are extremely important lessons in life, not just in dominoes. Who has not done this activity? How many of us have repeated it again and again and again until we finally achieved success? Has anyone given up domino stacking forever because of an initial, failed attempt? These are more than stealth lessons of observing physics in action. These are stealth lessons in precision and perseverance that no spelling workbook or math lesson can teach, even though precision and perseverance are required to succeed in both spelling and math. These are lessons of the kind that spurred the imaginations of Thomas Edison, Isaac Newton, and Benjamin Franklin, and caused them to wonder “what if…?”

Allow your students to combine components from a variety of learning aids and games, designing new ways to use them, and ultimately learning new lessons—stealth lessons. To restrict “learning aids” from being “playthings” is to limit learning. Another way to encourage further discovery-play is by innocently asking leading questions, such as “what would happen if you did this…” or “is it possible to stack those like this…?” You can take advantage of a teachable moment to add the appropriate vocabulary now, or you can wait until later, reminding them of their free-play adventures and relating those to the lesson concept of the day. Try not to spoil their fun by instructing your kids in how to play with these new-found toys, but let their imaginations drive them. Insisting they formally narrate what they’ve learned is another fun-killer, but do listen with interest as they excitedly volunteer details of their discoveries. By paying close attention to their stories, you’ll notice what they’ve learned—even if they don’t realize they’ve learned it.

Playing games requires some degree of thought, planning, or strategy, and that translates into stealth learning. Word puzzles based on quotations, axioms, and folk wisdom provide more stealth learning. Other types of puzzles teach logic, math, and other valuable skills through very stealthy methods. Play is learning, and learning can be play. Stealthiness connects the two.

See also:

A Day without Lessons

The Know-It-All Attitude

Homeschool Gadgets: An Investment in Your Future or a Waste of Money?

The Importance of Play in Education

The Value of Supplemental Activities

Is Learning Limited to Books?

Sorting toys Is Algebra

Gee Whiz! Quiz

Topical Index: Learning Outside the Books

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Recent Comments