How do you pack for vacation? My daughter used to pack one suitcase with her clothing and another suitcase just for her books. She would sit in the back of our van with her nose in a book, seemingly oblivious to the scenery passing by outside the windows. She might only make her way through a few of those books during a week-long trip, but her selections were varied enough to cover whatever need arose. She chose her reading material to closely coordinate with the vacation itself, and her favorite Zane Gray stories came alive as we drove through high desert country or deeply wooded forests. I’m sure that if we’d ever scheduled a boating trip, she would have brought along Moby Dick or perhaps Mutiny on the Bounty. Back at home, my kids often made use of their tree house as a reading hide-away. A blanket fort or tent might offer a different setting for “ambiance reading.”

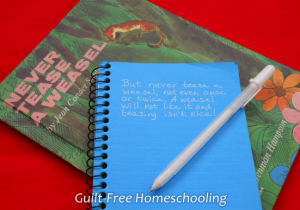

I enjoyed reading aloud to my kids, not for the exercise of reading aloud, but because I loved to watch their faces as the story turned suspenseful or to see them puzzling over what might happen next. Sometimes I stopped reading and asked for their opinions of what a certain character had just done or where they thought the plot might lead next. And then the reading would resume, only to reveal a twist that none of us had anticipated. We laughed, we cried, we paused to look up unfamiliar words in the dictionary, but mostly we shared the stories over and over as classic lines found their way into our conversations: There’s nothing like the smell of burnt marshwiggle to bring you to your senses, or It’s just a simple matter of mathematics.

Our lists of favorite books and favorite authors grew longer every year. Whether we had read them aloud or individually, our lists included: The Chronicles of Narnia and Out of the Silent Planet by C.S. Lewis (the rest of his Space Trilogy was a bit much for my youngsters, but they absolutely hung on every word of the first volume); A.A. Milne’s poems, Longfellow’s The Village Blacksmith and other poems; the Danny Dunn books (based on a young scientist/inventor); and the Elsie Dinsmore series by Martha Finley (28 books in the original series).

We discovered that watching the video version first (whenever possible), then reading the book was a big help to a reluctant reader. That method brings a quick understanding of the plot, setting, and characters—enough to hold the attention while the book releases it all much more slowly. Sometimes my kids wanted to read the entire book to see all the scenes that had been left out of the movie; sometimes they read only a chapter or a few pages to get a sense of the author’s writing style and the mechanics of how various elements were handled. Sometimes we just stopped a movie in the middle and looked for something more interesting.

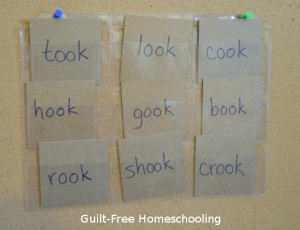

Poems, magazines, short stories, comic books and graphic novels can all be valid reading material. Shorter works instead of long chapter books can capture the attention and make reading less tedious, especially for boys and disinterested readers. Reading aloud to your child can also help build interest his interest—I did that with some shorter chapter books for early readers when my son was just becoming independent at reading. I’d read a few pages of the first chapter, then tell him he could read just a paragraph or two for himself while I went to shuffle some laundry. Then as I took my sweet time getting back, he would devour page after page, caught up in the story. Let’s just call it salting the oats to make sure the horse takes a drink.

To encourage your not-so-much readers to become I’m-running-out-of-books readers, try as many of these tips as possible. Help them choose some unforgettable lines from a few favorite books to print up, post on a wall, and quote to each other. Pick something from the following themed lists for a new genre to expand your readers’ interests. As the great Sherlock Holmes would have said, The game’s afoot!

Summer Adventures: Jules Verne, Frank Peretti’s Cooper Kids Adventure Series; J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings trilogy; Alexandre Dumas; Zane Gray; Robin Hood or the King Arthur stories by Howard Pyle; Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson; The Chronicles of Narnia and Out of the Silent Planet by C.S. Lewis.

Summer Romances: Robin Hood by Howard Pyle; Zane Gray’s westerns (heroic cowboys who always win the girl’s heart); Grace Livingston Hill; Jane Austen’s Emma or Sense and Sensibility.

Dark Summer: the mysteries of Agatha Christie; Edgar Allan Poe; Arthur Conan Doyle; Louisa May Alcott’s The Inheritance.

Summer in the Real World: biographies of the Wright Brothers, Thomas Edison, George Washington Carver, Abraham Lincoln, Copernicus, Leonardo da Vinci; Carry On, Mr. Bowditch; The Trumpeter of Krakow.

For a few more tips on encouraging your young readers, see these articles:

How to Adapt Lessons to Fit Your Student’s Interests and Make Learning Come Alive

Classic Literature Is Not Necessarily Good Literature

Teaching Spelling (and Grammar) Through Reading and Listening

Tests, Book Reports, and Other Un-necessities

Read the entire GFHS Summer Camp series:

Homeschool Mommy Summer Camp

Homeschool Summer Camp FUN!

Homeschool Summer Reading Activities

Homeschool Summer Scheduling

Encouragement Around the Campfire

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Recent Comments