[This article was written by Jennifer Leonhard.]

Is your student attracted to color or motivated by markers? Does your student struggle with staying organized when studying? Color-coding is a great learning tool. Visual learners respond well to color as an organizational method, and non-visual learners can improve their visual skills by using color to organize information. As classes become more complex in high school and college, color-coding becomes an even more valuable organizational tool.

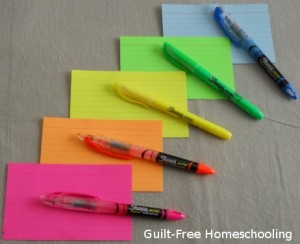

As a strong visual learner, I used assorted colors of index cards and highlighters to help me organize my thoughts and the material I was studying in my college classes. I used the order of the color spectrum as my color code whenever I needed to maintain a beginning-to-end, front-to-back sequence: red, orange, yellow, green, blue. My system always began with red (pink worked as the closest available color in note cards and highlighters) and proceeded through the spectrum to blue (violet/lavender was too hard to find in highlighters).

Here’s how I wrote the various parts of a speech or oral presentation: one pink card held the introduction, several orange cards for the information for Point 1, several yellow cards for Point 2, several green cards for Point 3, and one blue card held the conclusion. I could rehearse a presentation using these cards, and if I dropped them or they got mixed up in my backpack, I could easily put them into color spectrum order again. Any supporting quotes had their own index cards (using the appropriate color code for each point), and I would draw a squiggly outline on those cards to indicate that they contained the quotes. Each card had a topical title at the top and a number in the corner to indicate its order within each color group. I rarely ever needed to look at my note cards when giving a presentation, because I had them so well organized that I could easily see them in my head and go from there, but I did keep the cards with me in case of a blank-out moment. I could also turn them in to the teachers who asked for them as part of the assignment.

I also used this system for writing extensive research papers to create an outline in this format. I could put anything supporting Point 1 on orange cards and just go through all the orange cards later to put them in order for writing my paper. When doing research papers and printing out a stack of articles for a 50+ page paper, I would use highlighters in the same colors as my note cards to circle significant points in the article. I could then grab all articles with orange outlines and work just on my first point without being distracted by all the other sections. If an article had information for several points I would do a thicker outline in the color that it discussed the most and a thinner outline in the color of the point it discussed less, and then highlight or circle the section of text that pertained to each part in the appropriate color. I could flip through my notes very quickly and efficiently in this way and find exactly what I was looking for at any particular moment. I rarely had a “blanking” moment when writing, because I had a system that provided me with a place to start. I didn’t have to write the individual sections of the paper in any particular order, and if I found myself overwhelmed by the sheer amount of research information I had printed, I could simply start color-coding instead of freaking out. If I found myself unsure of where to stand on an issue or how to phrase my findings, I could simply grab all of the items outlined in orange and start highlighting, circling, or underlining the important sections that I wanted to use. Stuck on what to write for orange? No problem! Just work on the yellow items for a while, and then come back to orange later. I had no fear of getting confused or forgetting what I was doing next, because everything was very plainly color-coded for picking up where I left off.

Similarly, I would use this method to study complex material. I used the same color-code for highlighters, note cards, in my lecture notes, and in the text books, so that I could start the process while reading and know what to put on the index cards later. I used yellow as my color-code for keywords from the text. Pink was for any important dates to remember, green signified important people, and orange was for formulas and diagrams. Blue was for any other information I needed to make sure to remember. By categorizing things like this, I could pull out just my orange cards right before a test and review the formulas and diagrams, if I thought I was suddenly blanking on something. I’m bad at remembering specific dates, so I could grab the pink cards to quiz myself on those. This made it easier to categorize the test elements in my head, and instead of all the information being a blur of grey pencil notes on white lined paper, I could focus my memory on just the orange parts, or just the pink parts. The colors became just as important as the facts themselves, especially when trying to sort through all the facts in my head to find the one correct answer I needed on a test.

Whatever color-coding system you choose to use, the color significance can vary from subject to subject, but consistency within each subject is the key to making your system work. Yes, I bought a lot of index cards and highlighters, but they became valuable assets to my study habits, and the positive results proved their worth. Other colored items could also be added to a colorized system, such as colored pencils, file folders, pocket folders, notebooks, divider tabs, sticky-flag bookmarks, and whatever else your favorite office supply store has crammed into its aisles. Using color-coding is a great organizational and memory tool, and it strengthens your visual learning skills, even if visual skills are not your strongest learning style. And who doesn’t like playing with a whole rainbow of highlighters?

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Recent Comments