[This article was written by Jennifer (Morrison) Leonhard: Guilt-Free daughter and homeschool graduate.]

The holidays are a hectic time: relatives are coming over, the house needs to be cleaned, presents must be bought and wrapped, and food must be prepared. The schoolwork either gets lost along the way or becomes an added frustration as we try to get everything done at once. Mom planned our school schedule with the knowledge that Dad would be home from work around this time and regular schoolwork wouldn’t get done, but the learning was just beginning.

Mom usually gave us a break from lessons during the entire week of Thanksgiving, and we often stopped our official schoolwork well before Christmas, since extra time before each holiday was more beneficial for Mom’s preparations than time off afterward. However, we found many opportunities for learning, even when the schoolbooks had been put back on the shelf.

Shop Class

Dad usually did some project around the house during his time off from work (after all, you can’t get Dad to just sit around the house doing nothing). We learned to fix cracks in walls, paint, and generally drive Mom crazy with home repairs, all while she was preparing to have people over. Creating homemade presents, like building blocks, picture frames, and ornaments, teach handcrafts while theoretically cutting down on the expenses for gifts.

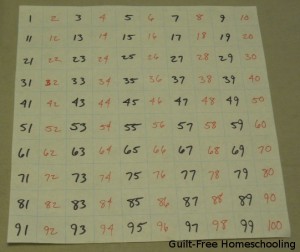

Math

Mom has always used cooking as math. Make a recipe smaller or larger, and you are automatically learning fractions: 3/4 cup of flour times 2 equals 1 1/2 cups. (Sure you could just use the 3/4 cup twice, but then what are you learning?) The economics of having a budget for Christmas will never fail to provide an opportunity for learning. How about learning some geometry and spatial relationships when wrapping presents? A lesson in possibility vs. impossibility lurks in the concept of a jolly and fat Santa squeezing down a chimney (which also brings up the lesson of “don’t try this at home”) or reindeer in flight (although one can argue that bees are also supposed to be a flight impossibility, and yet they consistently defy logical aerodynamics).

Music

Obviously, Christmas includes music — but that can take on many different forms. You can find many genres of Christmas music, from a symphony orchestra to the sounds of animals barking and mewing Away in a Manger. The latter is rather amusing the first time, but it gets harder to appreciate with frequency. The library and your friends will likely have a variety of holiday music that you can sample. I found a simple song book and learned how to tap out a few tunes on the piano. I knew what Christmas songs were supposed to sound like, so they were easier to learn, and I got a small taste of playing the piano. Explore the lyrics of Christmas songs to learn a little about Christmas history — have you ever wondered why the lyrics to I’ll Be Home for Christmas talk about presents on the tree?

History

Beyond the lyrics of songs giving us a glimpse into Christmas Past, there are many other subjects you can study for history. Thanksgiving is a history lesson in itself, from the voyage of the Pilgrims to learning why we celebrate it in November. American history becomes an interesting pastime instead of boring history when reading a Pilgrim’s personal account of coming to this country. Do you know why we celebrate Christmas around a tree? Or who started the tradition of sending Christmas cards? Do you know how the first Christmas trees were decorated — or the stories behind your family’s favorite decorations?

Literature

From studying Christmases past to reading about the Ghost of Christmas Past, ample literature can be found about others celebrating Christmas. In the spirit of the season, reading holiday stories aloud by a fire while drinking hot cocoa certainly doesn’t feel much like schoolwork!

Spelling

The holidays can provide much inspiration for spelling, from Old World words in songs to sitting around after dinner, playing Scrabble with friends and family. Reindeer pulling a sleigh will provide you with more exceptions to the rule “I before E, except after C.”

Language, Geography & Social Studies

Research the different names for Santa Claus around the world. (And for math, estimate the number of stops he must make in a single night.) Various traditions surround Santa’s visit, from cookies and milk to leaving shoes instead of stockings to be filled. And don’t overlook the traditions of Hanukkah: many interesting studies reside in the holiday celebrations from other cultures.

Cooking

Besides being recruited to help Mom with preparations for large family dinners (and vying for turns at grinding the fruits for our traditional cranberry relish), we often made a variety of cookies and candies to have available during the season. Occasionally, we also made an assortment of mini-casseroles and other freezer meals as gifts for elderly grandparents. Perhaps you could experience popular foods from holiday celebrations in the past — and who doesn’t enjoy a chance to try yummy new foods? You may end up adding a new favorite to the season, or (if you don’t like the new dish) you can at least learn to be more thankful for the old standards your family regularly prepares for holidays.

Many more lessons can be found in the holiday seasons — just make sure to keep your eyes open for learning opportunities and your heart open to the most important lesson of all: being thankful for the Son.

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Recent Comments