This is part of a series of articles based on actual questions I have received and my replies to them. Real names will not be used, and I will address my responses to a generic “Mom”; if you are a homeschooling Dad, the advice can usually be applied to you as well. The wording will be altered from the original letters (and often assembled from multiple letters) and personal details will be omitted or disguised in order to protect the privacy of the writers while still maintaining the spirit of the question. If you have a specific homeschooling question that you would like me to address, please write to me at guiltfreehomeschooling@gmail.com. If part of your letter is used in an article, your identity will be concealed.

Dear Carolyn,

I am trying to homeschool my children, but they do not respect me. They refuse to learn from me, simply because I am Mom. The teens do not set a good example for the younger ones. The teens stay up much too late, then need to sleep all day. We are struggling to get by on a single income and live in very cramped quarters. My husband works hard and comes home too tired to be able to help me with anything. I feel like I am doing everything by myself. Why am I doing this?

–Mom

Dear Mom,

I am so glad that you have written to me. I am sure you have thought about giving up at this point, but instead you have reached out for one more thread of hope. I have that lifeline for you.

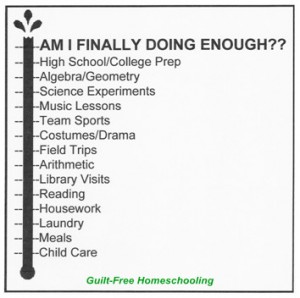

I will not pretend that I can offer a magic potion to make everything wonderful by this time tomorrow morning. The job ahead of you will be difficult, but it will be worth every drop of sweat and every tear you shed. I will list below several of my previous articles that will give you more insight into how to handle your situation. The order in which you read them and/or implement them is up to you, but I give the list as your homework. Some of the articles will address issues with your children, but others will address issues with you and your parenting role. The good news is that you can change your own attitude fairly easily.

Is this your first year of homeschooling? If so, the first year is always the toughest, no matter who you are. Do not become discouraged just because things are difficult during the first year — homeschooling becomes easier with each passing year as all family members learn the ropes and get accustomed to a new way of doing things. Students get used to having Mom for their teacher, and Mom learns the best ways to relate to each of her own children. It does not happen overnight, but perseverance will pay off.

I recommend spending time with your students, discussing and planning together for changes to your schedule for lessons plans and household chores. Shift your presentation of lessons to fit your children’s interests and help them get more excited about what they are learning. See Topical Index: Learning Styles for more help in this area.

As for the sleep schedules, are the older children staying up late because that is when Dad is home? Or are they just being undisciplined and defiant? There is no “rule” that homeschool classes must begin at 8am and be finished by noon. Adapt your lesson schedule to fit your family’s lifestyle: if Dad works a late shift and sleeps later in the mornings, you may be able to allow the children to sleep in and keep the household quieter for Dad’s sleeping habits. (I have included a link below that covers ways in which Dads can be involved with homeschooling without teaching formal lessons.) We knew one homeschooling family where the father worked a job that alternated shifts each week (week 1, days: week 2, evenings; week 3, nights; week 4, days; etc.). The Mom and children shifted their lesson times and sleep times as needed so that Dad and the children would always have opportunities to be together. It was difficult, but the relationship of father and children was more important to them than others’ opinions were, and they slept late or rose early to be able to have family times together.

Mom, this is a battle worth fighting, but the enemy is not your children. The enemy you are fighting is anything and everything that keeps your family from drawing closer together. Seeing that perspective can help you identify trouble spots more easily. Browse through the Titles Index and read anything else that catches your eye and scan through the topics covered in the Topical Index. You may especially benefit from the comfort offered in the Encouragement for Parents section.

And now, your homework assignment:

Respect Must Be Earned

Second-hand Attitudes

Meatball Education: Filling in the Potholes of Public School

Surviving the First Year of Homeschooling after Leaving Public School

Parent Is a Verb

If You Can Present Your Case with Facts and Logic and Without Whining, I Will Listen with an Open Mind

Limiting “Worldly” Vocabulary

Family Is Spelled T-E-A-M

Siblings as Best Friends

Involving Dads in Homeschooling

Who Wrote This “Rule Book” and Why Do I Think I Have to Follow It?

Homeschooling Is Hard Work

Reschedule, Refocus, Regroup

Redeeming a Disaster Day

We’re Not Raising Children — We’re Raising Adults

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Recent Comments