I went to public school for my education. It was a rural school with Kindergarten through twelfth grade all in one rather small, three-story building. The teacher-to-student ratios were fairly low, since most classes rarely exceeded twenty students. Most of the teachers used traditional methods of oral lectures and reading assignments.

I remember feeling detached from the rest of the class, because I was either way ahead of the teacher or way behind. In Kindergarten, I could already read enough to know what the workbooks said, and I could tell when my teacher was changing those directions and leaving out the parts that I thought sounded like more fun than what she wanted us to do. I had to sit and wait and sit some more, surrounded by a roomful of enticing learning toys that could never be touched. And my teacher insisted that sitting quietly and listening quietly were the best and only suitable ways to learn anything.

In fourth grade, I knew nearly all of the spelling and vocabulary words before my teacher wrote them on the board, but she often mispronounced them. I had my very own personal dictionary in my desk, something I loved to read more than any of the storybooks on the classroom shelves. I pulled it out one day to show my teacher what the correct pronunciation of a certain vocabulary word was, because I thought she would want to teach things accurately. Instead, she just got upset. For some unknown reason, we didn’t get along for the rest of that year.

In sixth grade, I had a very old, very worn out teacher. She had her methods that she had used for decades, and she expected them to work forever and for every student. She also had certain subjects that she didn’t care to teach, so she glossed over them with the same three words for every assignment: “Outline the chapter.” I learned nothing from geography that year, except that I could not possibly produce an outline to her satisfaction.

Occasionally, a random teacher would allow us to do a special project as an assignment, but it didn’t happen more than once every few years and never in more than one subject. Any project was also limited to about a week in length and still had to meet that particular teacher’s expectations. The year I prepared a typical Medieval meal for my World History teacher, I thought he was going to have a stroke right there in the classroom. He seemed very concerned that I had smuggled some beer into the school building, until I whispered to him that his tankard contained cream soda as a visually-similar substitute. Despite all my research into the types of foods, serving utensils, and customs common to the time period, he didn’t know how to grade my beef stew and fake beer. He was much better with salt-dough castles and cardboard armor.

All in all, I hated school. I hated the teachers who treated me with contempt for daring to want something other than outlining the entire geography textbook and droning through random passages from Shakespeare read aloud in class. I hated the endless repetition, year after year of boring textbooks that all said the same boring things. I hated it all.

Once I had my own children, everything changed. I loved watching my kids discover the world for the first time. I loved the expression of recognition on their faces each time something new began to make sense. We played games, we played house, we played dress-up, we played everything we could play. We made forts, we made cookies, we made make-believe. We read stories and more stories until we knew them by heart, and then we recited them together when the books weren’t close at hand. I read them simple stories, pointing out the details in every picture. I read them chapter books beyond their years, allowing them to meet brave explorers like Christopher Robin and form pictures in their minds of what “heffalumps” and “woozles” must look like. I read them the lyrical poetry of A.A. Milne, Edward Lear, Robert Louis Stevenson, and countless others. And then suddenly they were old enough for school.

When I sent my children off to public school, they fit into their classrooms just as well as I had in mine, which is to say “poorly.” They wanted to play with the hundreds of wooden blocks at the back of the classroom, instead of sitting at the teacher’s feet as she did yet another mind-numbing counting-to-ten exercise. They had to endure adding 1 + 2 + 3, being told it was difficult and challenging, when they had already figured out how to do 2-column subtraction in their heads. They had to sit and wait and sit some more, surrounded by a roomful of enticing learning toys that could never be touched. And their teachers insisted that sitting quietly and listening quietly and reading quietly were the best and only suitable ways to learn anything.

When my husband and I made the decision to remove our children from public school to begin homeschooling, I used the traditional school model of textbooks and worksheets, simply because it was the only thing any of us had ever known. There I was, ordering boring curriculum, assigning boring lessons, and grading boring worksheets, doing all the same things I had hated all through my own school years and boring my own children with every step.

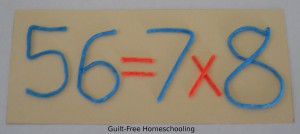

My students began stumbling over what I called “potholes”—missing portions of vital information that their former teachers had failed to impart. My 5th-grader was delighted to discover that anything she hadn’t understood at public school could be re-studied at home without penalty or ridicule, and she provided me with a list of math concepts that she wanted to master, including fractions, decimals, percents, and measurements. Specialty workbooks helped us fill in those gaps, but actual practice in real life experiences gave the concepts purpose. We measured dozens of things around the house, maybe hundreds of things. We converted the measurements into fractions and decimals. We converted the fractions and decimals into percentages, until it was apparent that the different forms were just “nicknames” for the same amounts. Manipulating the numbers became fun, and math lessons became less intimidating.

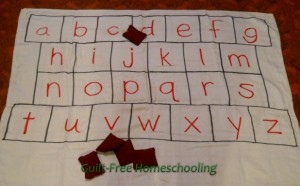

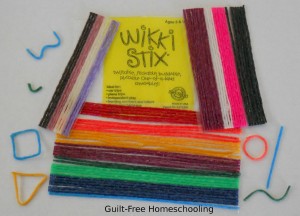

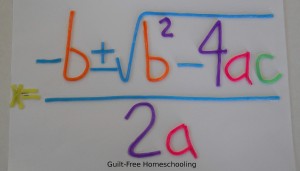

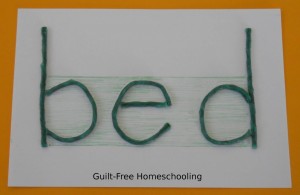

I realized that my children were benefiting from the hands-on experiences that solidified what the textbooks had to say. When a math problem spoke of so many red trucks and so many blue trucks, and my child wasn’t understanding it, we used colored blocks to illustrate the problem in a way she could do over and over again until she got it. When my daughter couldn’t solve an anagram for her spelling lesson, she took the letter tiles from the Scrabble game and rearranged them until she figured out the word. The enticing learning toys gave the lessons tangibility, and the fingers understood what the eyes had missed.

I haven’t met a spelling curriculum yet that I like. Phonics is a systematic method for learning to read, but why should that be followed by repetitive lists of spelling words that anyone with a decent grasp of phonics could spell without difficulty? Vocabulary words were never much different from the spelling words. If my students could break the word down into its phonetic components and learn to read that word, either they already knew its meaning, or we would look it up in the dictionary together.

As a child, I had loved having my own personal dictionary, which I routinely browsed for new words. That was the basis of my own vocabulary expansion. Using the pronunciation guides, I could learn to read any word I came across, and the definitions, origins, and various forms of the words added even more to my personal studies. My son picked up this habit himself and regularly quizzed me with new words he had discovered, trying (usually unsuccessfully) to stump Mom. Reading material is an excellent source of new vocabulary words – if it’s not, then your students are reading things that are too simple for them. Another personal habit of mine is to keep a dictionary and pencil close by while I’m reading. Any unfamiliar words get their definitions written in the margin of the book. (Don’t tell anyone, but I’ve even been known to pencil a definition in the margin of a library book, reasoning that if I didn’t know that word, the next reader probably wouldn’t know it either and would be grateful for the notation.)

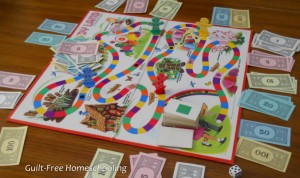

No matter how many curriculum programs we tried, nothing was a perfect fit for us. The textbooks were too boring and too far removed from everyday life. We supplemented the textbook studies with activities, games, and field trips, and we always found that we learned much more from the extra activities than we did from the textbooks and workbooks. Even the math texts that provided solid teaching were tedious in their repetition-without-application. Board games could always be counted on for practice in the same concepts, but with much more enjoyment. Although we enjoyed a wide variety of supplemental activities, most of the time we stuck to a pretty structured sequence of academic studies. It was only toward the end of our homeschooling journey that I began to research and understand learning styles and see the full value and effect of alternative types of study over traditional methods.

Today, I’m much more likely to recommend family activities, a video-and-discussion session, or a round of board games instead of textbook lessons. How did I get to this point? When did I become an unschooler? If we had it all to do over again, we would probably be more like that eccentric unschooling family we met when we first started homeschooling—their spontaneous and unconventional approach to learning did not fit into my definition of education at all (but they did seem to be having a lot more fun at learning than we were). We would read more biographies from the library shelves, instead of purchasing over-priced textbooks that barely scratched the surface of any remotely interesting topics. We would spend hours dropping Mentos into Diet Coke, instead of just watching the You Tube videos. We would have all sorts of wonderful fun, we would learn all sorts of wonderful things, and we would enjoy journaling all our wonderful exploits, because we would be making and documenting real history instead of slogging through yet another tedious assignment made up by some stranger who knew nothing about us or our interests.

The way I see it, looking back over many years of actively homeschooling and many more years of mentoring homeschoolers, if a student can learn something well by reading it in a book, he doesn’t need anyone’s help. On the other hand, if a student is struggling to learn from reading and struggling to learn from discussions and explanations, that student needs a hearty dose of unschooling methods. Get elbow-deep in an experiment, work out a physical representation of a math problem with some type of thingamabobs, watch someone demonstrate a real-life skill and ask them to help you learn it step-by-step. Going places, seeing stuff, and doing things are much more valuable methods of learning than just reading about someone else going places, seeing stuff, and doing things. If unschooling means leaving the books behind and getting out there to learn from life itself, then I’ll happily call myself an unschooler. I never did fit into a classroom very well.

[For a further explanation of educational potholes, see Meatball Education: Filling in the Potholes of Public School]

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Guilt-Free Homeschooling is the creation of Carolyn Morrison and her daughter, Jennifer Leonhard. After serious disappointments with public school, Carolyn spent the next 11 years homeschooling her two children, from elementary to high school graduation and college admission. Refusing to force new homeschooling families to re-invent the wheel, Carolyn and Jennifer now share their encouragement, support, tips, and tricks, filling their blog with "all the answers we were looking for as a new-to-homeschooling family" and making this website a valuable resource for parents, not just a daily journal. Guilt-Free Homeschooling -- Equipping Parents for Homeschooling Success!

Recent Comments